Most of the glyphs and paintings are located inside caves, near the entrances; sometimes, in areas of difficult access. The caves in this area have not only been the main source of fresh water, fundamental for the development of the Maya culture, but also became the places where the religious ceremonies were performed. The oldest representations are those in Chiapas, and in the Lacandon Rainforest they remain sites of pilgrimage.

In Yucatan’s Puuc Route, some caves have been proven resting places and ossuaries have been found. Art depictions feature mainly elements related to death. Near Tizimin, in Pool Balam cave, a carved stalagmite is preserved; it functions as a solar calendar, signaling equinoxes and solstices.

Figure 1 Painting in a Cave near Puuc Route. Yucatán. © Sergio Grosjean

A cave that we can visit as a tourist attraction is Loltún, also in the Puuc Route. This long cave system has been continually used by humans since 9,000 BC., and as a dwelling space since then until 1500 AD. There is proof of its first use as a domestic space, the development of agriculture and farms; and in the past 500 years with the development of human settlements, its use mainly as sources of fresh water. There have been located 145 mural paintings and 42 carved glyphs inside Loltún.

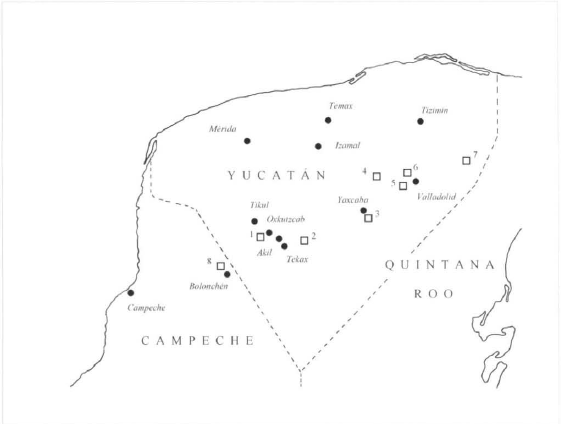

More sites with paintings have been preserved than those with carved glyphs. In Yucatán, the art appears to have been produced during the Classic period. In an area known as the Ticul Hill, the highest point in the Peninsula, they display a particular style. Besides Loltun, four other caves have been found with thick lines and rigid figures, in black and red. A constant feature is faces, heads or skulls and the glyph for the four directions, a crossroad. In the Postclassic period, and the beginning of the Colonnial time, the figures become simpler and they latinize, imagery from European origin is also preserved. Unfortunately, many places have been vandalized with graffiti. Loltun has been preserved precisely after becoming an orderly tourism service that can therefore preserve the legacy caves represent.

Figure 2 Caves with art depictions in Yucatán and Campeche. © Matthias Strecker

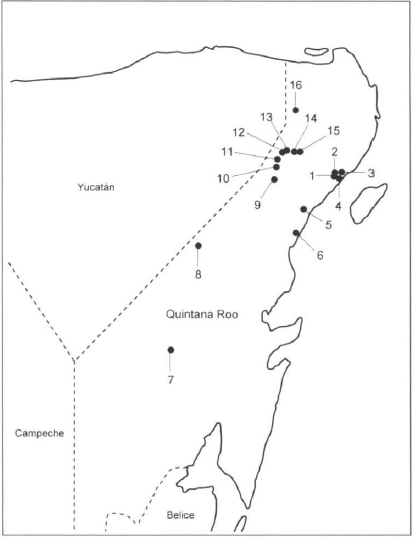

In Quintana Roo, the Riviera Maya has many caves with carved glyphs, some inside private property but some open to the public, such as Punta Venado and Tankah. In a cave near Kantemo, the cave of the hanging snakes, an 80 cm face is painted in black pigment. Near Tihosuco, eleven positive handprints in red and black are preserved. In the villages near Coba carved features, mainly faces are not easy to locate, but nonetheless feature the early human occupation of caves.

The precise location of many sites with art depictions remains confidential, to preserve them from being vandalized. But the simple notion that these caves have been used for over ten thousand years in a row is reason enough to visit the area and to connect with them, in recognition of their contribution to the development of our culture. However, the urgent need to protect and preserve these caves, while also educating the visitors and local people to not impact these sites when they try to carve their initials.

Figure 3 Caves with art depictions in Quintana Roo. © Dominique Rissolo

There is an area of great importance, for the development of the Maya culture, and that is the Zoque region, located at the intersection of Veracruz, Tabasco, and Chiapas. In the archaeological site of Malpasito the boulders with carved glyphs are quite abundant.

It has been determined that the sites with carved glyphs were created during the Formative Early Pre-Classic period, and the sites with paintings during the Early Classic period. The Northeastern and Eastern sites are clearly Maya, and the Central and Western sites are related to the Zoque people. The paintings preserved in Cerro Naranjo present some influence of the Post-Classic Mexican highlands. Some colonial art displays can be spotted in Rio Sabinal.

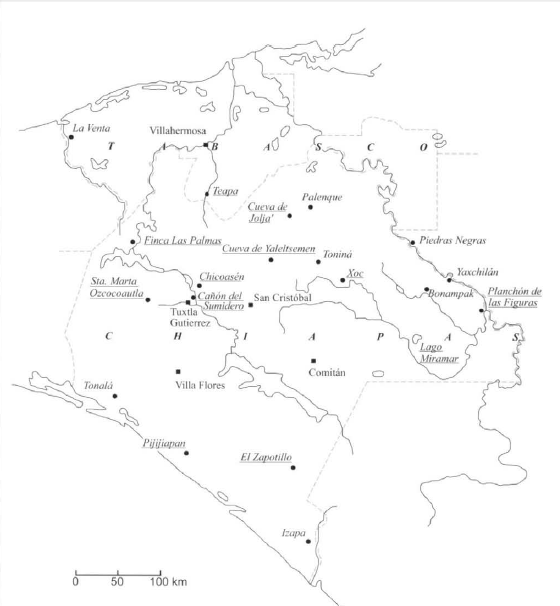

Figure 4 Location of some caves with art depictions in Chiapas andTabasco. © Matthias Strecker

It has been determined that the sites with carved glyphs were more commonly public places; while those with paintings are in caves with difficult access and appears to be visited by a reduced number or worshippers. Art depictions inside caves continued until last century, and some elements are clearly colonial and from the rise of the republic.

The cave of Jolja, in the region that divides Chiapas and Tabasco, has been protected by the local community, by securing the entrance and controlling the access.

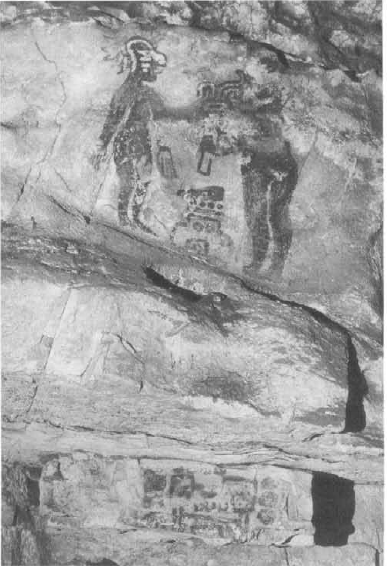

Figure 5 Maya gliphs in the caves of Jolja’, grupo 5 © Karen Bassie.

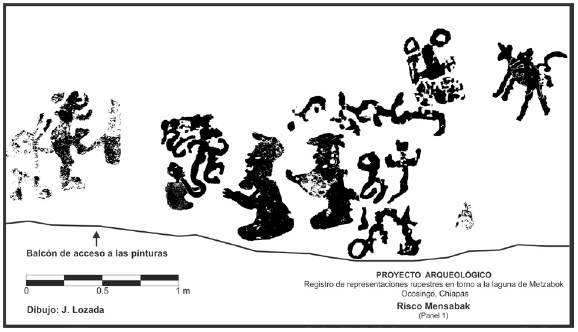

The Lacandon area keeps sites of great importance created during the Pre-Classic period, and that are still being visited by the last guardians of their faith. The Metzabok lake, located in the Ocosingo region is defined by its karstic features, has three important cliffs around it. In Tsibaná, there are 56 paintings from different times and motifs; in Mensabak, there are 113 paintings in eight different panels; in black, orange, and red; representing ritual events, perhaps an ascension to the throne of a young ruler surrounded by jugglers and priests.

In another area, negative handprints over four meters high must have been stamped by agile people with the ability to climb rocks. In O’ton K’ak, there are 19 graphisms, mainly anthropomorphic figures in five panels, some of them above 10 meters from the level of the lake. In Panel 1, a carved face with eyes and mouth also decorated in red paint might represent K’ak, the Lord of Fire, that wore his face painted in blood.

This area of the Lacandon Rainforest has three more sites of transcendence; Tsibana, Mirador and Noh Kuh, that can be traced to the Late Pre-Classic period and that during the Late Post-Classic period continued to be pilgrimage sites or contained small settlements of people that kept using the caves as shrines until the late XIX century.

There are records of modern pilgrimage, by present-day Lacandon tribe to this and other cliffs, to perform religious rituals where the paintings are located. They recognize this caves as entrances to their sacred places and declare that the handprints towering above were made by the deities that dwell inside the caves.

Figure 6 Mensabak panel 1 at Metzabok lake. © J. Lozada

As visitors, we must consider that we are reconnecting with the origins of our civilization; and that the simple fact of being near these caves is an honor. We must promote that these sites are recognized as Humankind Heritage sites so they can be protected and preserved for another ten thousand years.

There are still many treasures to be discovered; there are many places that are not touristic, but that offer exceptional landscapes, full of history, and that we can reach one by one; bringing tourism one step beyond, always in a safe, respectful, sustainable and responsible manner.