Places like these are common in travel catalogs; however, they are treasures of Earth’s biodiversity and our obligation as tourism providers is to actively engage with the preservation of the natural capital of our planet. Nature-based tourism cannot be performed carelessly; it must adhere to standards and regulations that favor conservation; it needs proper supervision and a correct development from the start, or it will not prosper. Digital platforms for networking and support have become fundamental in achieving sustainability at the tourist destinations no matter their size or their location.

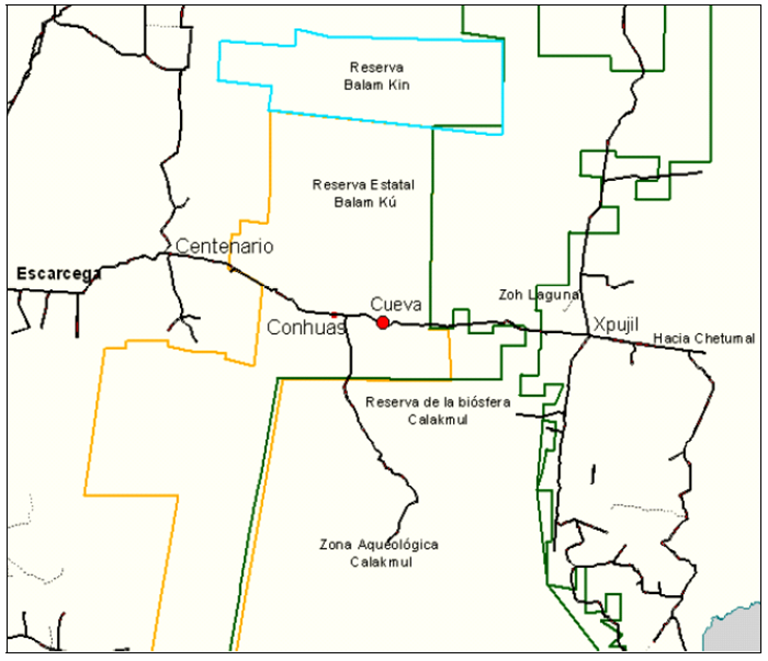

The Bat Volcano, Balam ku, Calakmul, México.

Bats dwell in caves, crevices, or hollow trees. Near the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, at the Balam ku Natural Protected Area, right next to the road connecting Quintana Roo and Campeche, a cave called the Bat Volcano, not a volcano, hosts around two million bats from at least eight different species of which seven feed on insects; so, their contribution to agricultural pest control is massive. On the contrary, the local use of agrochemicals is detrimental to the health of bats that feed on contaminated insects; and therefore, on birds of prey that feed on contaminated bats, creating a biomagnifying effect. The cave also sustains human pressure, mainly due to unregulated visits, and unjustified environmental alterations such as the trimming of the bushes around; also, by transit; and soon, by the planned new train tracks.

Figure 1 The Bat Volcano location.. Balam-Kú, Calakmul. ® Conabio BJ002

Confounding a breathtaking Nature display with a tourist attraction not always yields the best results; specially if it develops without the proper professional supervision required. In this particular location, people come and go inside a very health-hazardous cave, stand on the entrance of the cave while bats are flying out to feed, and sometimes even snap shots with flashes of the bats unsupervised. The most frequent visits are during the spring and summer breaks, which coincides with the breeding season and the breastfeeding of the newborns. Straightforward conservation actions are required.

Caves are hazardous places. They have a precise function for local biodiversity, and human interaction should consider many factors; but most visitors are not aware of the common restrictions and do not comply with the basic personal protection measures required. Inside caves, it is common to find high levels of methane, CO2 and spores that thrive on organic decay and cause a severe pulmonary disease that is quite difficult to treat; we might be aware of coronavirus, but it is not the only one. People that wander inside the cave at sunset to watch the bats are not only unknowingly risking their health; but also the balance of the place, by disrupting a natural process when they get too close to the bats.

Access to this cave should be restricted to researchers, and a lookout area must be designated. There is a need for a custodian to remind visitors to respect the area and to do not wander inside, do not alter the plants around it and above all, to maintain a respectful distance from the bats. We have access to an exceptional area, the whole Calakmul region, and if we are neglectful, soon we will have nothing but the memory of what it once was.

The Cave of the Hanging Snakes. Kantemó, Quintana Roo, México.

Kantemó is an outstanding example of sustainable community-based tourism. Located in a remote area in the Yucatan Peninsula, the orderly vision they had from the start has made them stand out among the many other locations started up by the National Commission for the Development of the Indigenous People over a decade ago. Kantemó consolidated as a resilient project, well cemented in firm bases of environmental education and community development.

Figure 2 Kantemó, the cave of the hanging snakes. © Peninsular Alliance for Community Tourism

Inside the cave six species of bats feed the constrictor snakes that hang from the crevices on top, among scattered marine fossils. Below, crystal clear streams harbor the only living beings of the abysmal underground: the blind shrimp (Creaseria morleyi), the blind eel (Ophisternon infernales), the Mexican blind brotula (Ogilbia pearsei) and the cirolanid cave isopods (Creaseriella anops). On the surface, when the Ice Age shelves melted, a strip of the Holocene sea, saturated with calcium sulfate –unlike the calcium carbonate underground waters– created the Chichankanab lagoon system, now a Ramsar Site very near the Balan Ka’ax Natural Protected Area.

Figure 3 Chichankanab Lagoon. Ramsar site. © Consejo Civil Mexicano para la Silvicultura. (CCMS)

With the trusted advice of remarkable biologist Arturo Bayona, the local people created a cooperative to provide the tourism services; they purchased specialized gear: helmets, visors, canoes, bicycles, and everything needed for adventure tourism; they organized, trained, and distributed the tour operation, management, maintenance, and conservation of the environment; some became certified nature tour guides and learnt English; ecological compost toilets were installed; also, two palapas and a dining area for visitors. It is a business model worth supporting and replicating.

To complement the visit to the cave, an Educational Trail was developed, for walking or biking; and it is an ideal site for spotting any of the over 95 migratory birds in the area. You can also float away endlessly in a canoe on a lagoon as ancient as the ice age. It might seem Kantemó is in the middle of nowhere, but it certainly is near very important places.

Figure 4 Chichankanab Lagoon Sysem Aereal view. © Gulf of California Marine Program

Such wonderful places face the challenge of being in remote areas far from the hotel zones and other touristic places; since many potential visitors do not venture more than a couple hours away from where they are staying. However, the thrill of reaching such secluded places should be one of the reasons we plan such a trip. Digital platforms become crucial by directly helping potential customers learn more about the places they are visiting, including pictures, driving directions, or other services available such as accommodation and meal options. They also are fundamental in the strengthening of the professional abilities of the developers of the ventures listed, by integrating them in a specialized network that can grow and learn together, sharing experiences and expertise, helping on sales techniques and channels; they make it possible to prosper as a guild, and polish the skills of each project’s team leader.

Both the locations described above reflect two different paths Nature-based tourism can follow; while Kantemó must become a reference frame for community-based tourism, the vulnerability of the Bat Volcano in Balam kú ought to encourage us to prevent that wrongly managed tourism undermines the potential of the Yucatan Peninsula as a wildlife haven. What has become clear, is that the involvement of the local community is crucial in the adequate and sustainable development of an area or tourist venture or else it will fail.

As tourism providers, or users, we must adhere to regulations; and promote that they are clear, visible to visitors and widely known and understood. As conscious travelers we must educate ourselves about the places we are visiting, reasoning on why we are going there and what we will leave behind. Tourism is an exchange of experiences, not a product that can be bought and discarded at the end of the day. What happens in a trip remains inside us, inside those that interacted with us, and stays in the places we visit, forever.

For further Reading and reference:

Escalona Segura G. et al. Programa de manejo de la cueva “el volcán de los murciélagos” Calakmul, Campeche. 2010/07/13-2013/06/30. ECOSUR, FCQB_UAC, Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UAC, EPOMEX-UAC, UAT. Consejo Estatal de Investigación Científica y Desarrollo Tecnológico de Campeche. Recuperado de: https://www.ecosur.mx/ecoconsulta/busqueda/detalles.php?id=54014&bdi=0

Escobedo E y Calme, (2005). Informe final Subproyecto Néctar SNIB-CONABIO BJ002. México.http://www.conabio.gob.mx/institucion/proyectos/resultados/InfBJ002_murcielagos.pdf

Gulf of California Marine Program (2018) Chasing Mangroves Across the Yucatan Peninsula. Blog, Coastal & Marine, General. 06/14/2018. Disponible en: http://gulfprogram.ucsd.edu/general/chasing-mangroves-across-the-yucatan-peninsula/

Kantemo Beejkaxha Turismo Comunitario (2014) Historia de la cooperativa de Kantemó. Disponible en: https://kantemobeejkaxha.wordpress.com/2014/08/05/historia-de-la-cooperativa-de-kantemo/

Morales, J.J. (2014) Serpientes y ecoturismo comunitario. Supermexicanos.com Disponible en: https://www.supermexicanos.com/catalogo/kantemo/

Tecnológico Nacional de México (s/f) Arturo Bayona, un hombre que llegó a Quintana Roo para trascender. Sitio Web. Disponible en http://www.dgest.gob.mx/culturales/arturo-bayona-un-hombre-que-llego-a-q-roo-para-trascender

Vargas, J. et al. (2012) Conservación de Murciélagos en Campeche. Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología 3(1):53-66 DOI: 10.12933/therya-12-56 Recuperado de: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275497092_Conservacion_de_Murcielagos_en_Campeche