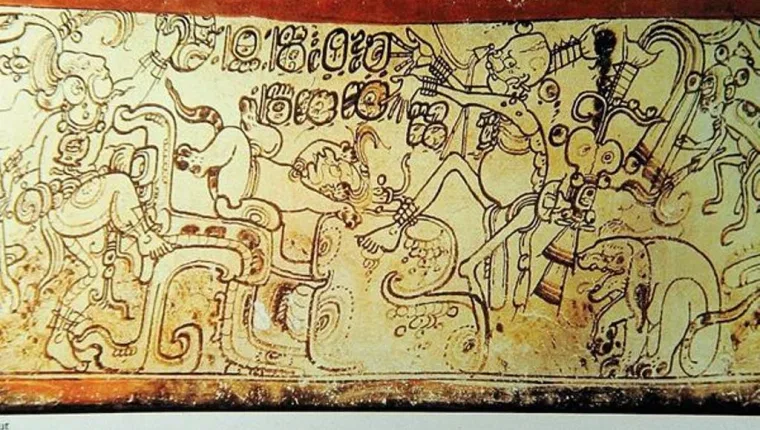

Figure 1 Pottery decorations with motifs from the Popol Vuh . © Hemeroteca Prensa Libre

Popol Vuh has a passage that describes Xibalba, and it is basically the description of a cave; there is a dark chamber where there is no light; a gallery where wind blows all the time and the cold is numbing; a chamber with roaring beasts gathered there; then a house full of bats, squeaking and flying around en masse, finally, a gallery with spears every inch, much like the stalagmites and stalactites that we can see inside caves.

.

Figure 2 Speleodivers exploring an inundated cave. © Proyecto Gran Acuifero Maya (GAM)

The Popol Vuh narrates how the epic twins Hunahpú and Ixbalamqué defeated the Lords of Xibalba and emerged from that cave to become the Sun and Moon. Popol Vuh is a rich saga that preserves many creational myths, and it is a must read for anyone interested in the Maya culture.

The idea of traversing the realm of the afterlife and defeating Death is part of many ancient cultures, and the Maya, with its breathtaking underground galleries is no exception; and in its more recondite places many offerings and millenary shrines have been preserved; and most still need to be found.

The first settlers of the Yucatan Peninsula who eventually consolidated in the Maya city states began their cultural awakening inside caves that we can now visit one afternoon, but which would fuel our imagination for days. Along the thousands of years that caves have been used as shelters, skeletal remains of those who perished inside have been found by explorers, both modern and ancient. In the origin of the Maya culture, those findings developed into funerary rituals and adorations that became more complex in time, and with the Spanish invasion blended with Medieval Christian rites. The Day of the Dead celebration is still observed ardently; and in Pomuch, a small town in Campeche, the people gather in the ossuaries to clean the bones of their deceased ancestors.

Figure 3 Day of the Dead Rites. Pomuch, Campeche, México. © Juan Antonio Martínez

The caves in the Yucatan Peninsula, and the whole Mesoamerica treasure the earliest testimony of our process as a culture and a Civilization. We are barely beginning to understand the value they hold to the Maya, as a path to prosperity. There is much to be learnt, discovered, explored, mapped, and scanned. However, if we do not assimilate their massive importance, all will be lost to vandals, pollution, or irreversible damage caused by urban sprawl.

Caves deserve all our respect, and we must protect them as they sheltered us in the awakening of humankind. Let us go back to where we really come, the caves.

The Yucatan Peninsula, and the Caribbean coast are peppered with caves and cenotes, most of them connected. Water flow is multidirectional, and the hydrogeological system is very dynamic. Being above it is a huge responsibility, not to disrupt it and preserve it with reverence.

Caves and cenotes were used as ossuaries, and in some cases, human sacrifices were performed. In the Sacred Cenote in Chichen Itza, sacrificial victims are both male and female and from infants to adults; but in many other caves and cenotes, the skeletal remains were positioned inside posthumously, and in some cases, while the level of the water inside the cave was much lower.

The skeletal remains have been found both articulate and inarticulate; and a peculiarity is that the skulls have been ritually modified during infancy, a common practice in pre-Hispanic cultures.

Figure 4 Speleodiver exploring an inundated cave or cenote. © Jerónimo Avilés, Banco de Imágenes INAH

Tourist diving in cenotes with archaeological findings is not permitted. However, there are plenty of options based in Responsible Tourism that facilitate our Experience inside this unique feature when we visit the Yucatán. Cave diving requires an international certification, but snorkeling is rewarding enough, and the views are as enjoyable as diving.

Immersing ourselves in the crystal-clear water of a cenote shakes us from our wiring with the outer world. The dark cavern transports us to a different dimension, with no light, no sound, no other life apart from us, and we find ourselves again in a womblike environment, nurtured by healing water; and if we are lucky enough to find a living cave, caressed by the dropping sacred water from the stalactites, the beating heart of Mother Earth.

For Further Reading and Reference:

Carrillo Gonzalez J. (2019) Los umbrales de lo proscrito. Ritualidad y simbolismo en torno a las cuevas y cenotes entre los mayas peninsulares Trashumante. Revista Americana de Historia Social, núm. 14, pp. 30-53, Universidad de Antioquia. https://www.redalyc.org/jatsRepo/4556/455660699002/html/index.html

Monroy Rios E. (s/f) El Sistema Cárstico-Antropogénico De La Península De Yucatán. Northwestern University. Disponible en. https://sites.northwestern.edu/monroyrios/entradas-en-espanol/sistema-carstico-antropogenico/

Manzanilla, L. (1994) Las cuevas en el mundo mesoamericano. Ciencias Núm. 36 octubre-diciembre 1994. p. 59-66. México https://www.revistacienciasunam.com/es/189-revistas/revista-ciencias-36/1777-las-cuevas-en-el-mundo-mesoamericano.html

Rojas Sandoval, C. (2009) Los cenotes como sitios funerarios. Espacio profundo 97 p. 10-13 Ciencia y Cultura INAH https://sds.yucatan.gob.mx/cenotes-grutas/documentos/el-inframundo-parte2.pdf